21/12/2014

18/12/2014

Retábulo - Casa de Santos

...Quando vemos ou ouvimos o

sino de uma qualquer torre de igreja, a nossa atenção é convocada para um lugar

e uma arquitetura diferentes de tudo o resto. O nosso pensamento desloca-se

inevitavelmente para o espaço interior que um templo delimita e para as coisas

sagradas que guarda. Coisas visuais feitas de cores, texturas e formas,

permanentemente cuidadas e usufruídas por comunidades regionais com consciência

do «valor essencial» e do «bem coletivo» que possuem....

06/07/2014

Colonos e periferias

Numa conversa de corredor

De conteúdo sério que há muito se desvaneceu

O que me sobressaiu foi uma afirmação entre vírgulas.

..., Eu até sei pintar!,...

Uma interrogação:

Que coisa grande e recente estará por detrás desta afirmação?

Só hoje a descobri.

E confirmei!

A obra existe e produz efeito muito antes de ser vista.

Antes tinha percorrido a livraria do CCB

Livro após livro, lombada após lombada, tudo foi visto.

Tudo em língua inglesa, pouco em francês.

E nenhum sobre assuntos e autores portugueses

Duas exceções: dois artistas portugueses escritos em inglês.

Uma livraria igual a todas as livrarias de qualquer museu ou

centro cultural à moda da Europa ocidental.

Mas pior por ser muito menor e pouco atualizada.

Conclusão:

Não temos artistas portugueses, não temos arte portuguesa,

não temos cultura portuguesa.

Minto: temos dois!

Alegremente, aceitamos ser PERIFERIA. Aceitamos

reconhecidamente a paternidade do COLONO inteligente, iluminado e nosso amigo.

Um perigo mascarado de internacionalização.

02/07/2014

Santa Bárbara de Nexe

I.Salteiro, 2014

Santa Bárbara de Nexe

Apesar de o mundo ser simultaneamente

imenso,

macro

e heterogéneo,

tentam fazer-nos passar

a ideia

de que ele é global,

plano

e homogéneo.

E quase sempre o

conseguem, com muito êxito!

Esta circunstância cria

a perigosa sensação de conhecermos o mundo,

quando afinal o que

conhecemos

são,

quando muito,

pequenas versões desse mundo.

Mas são estas «versões»

a imposição

com a qual intimamente

me insurjo.

Prefiro ser livre!

Somos um centro do mundo

e temos direito à nossa

versão do mundo.

É muito difícil

compreender por que razão nos escusamos a aceitar esta verdade tão óbvia, para

aceitarmos,

por questões de mero

comodismo,

as versões do mundo dos

outros.

Admitindo sermos vulgares

habitantes da caverna de Platão.

O que não devemos

ser!.....

Ilídio Salteiro, 2014.

14/05/2014

Aberto Caeiro, Seja o que for que esteja no centro do Mundo......

Alberto Caeiro

Seja o que for que esteja no centro do Mundo,

Deu-me o mundo exterior por exemplo de Realidade,

E quando digo "isto é real", mesmo de um sentimento,

Vejo-o sem querer em um espaço qualquer exterior,

Vejo-o com uma visão qualquer fora e alheio a mim.

Sim, antes de sermos interior somos exterior.

Por isso somos exterior essencialmente.

Dizes, filósofo doente, filósofo enfim, que isto é materialismo.

Mas isto como pode ser materialismo, se materialismo é uma filosofia,

Se uma filosofia seria, pelo menos sendo minha, uma filosofia minha,

E isto nem sequer é meu, nem sequer sou eu?

Seja o que for que esteja no centro do Mundo,

Deu-me o mundo exterior por exemplo de Realidade,

E quando digo "isto é real", mesmo de um sentimento,

Vejo-o sem querer em um espaço qualquer exterior,

Vejo-o com uma visão qualquer fora e alheio a mim.

Ser real quer dizer não estar dentro de mim.

Da minha pessoa de dentro não tenho noção de realidade.

Sei que o mundo existe, mas não sei se existo.

Estou mais certo da existência da minha casa branca

Do que da existência interior do dono da casa branca.

Creio mais no meu corpo do que na minha alma,

Porque o meu corpo apresenta-se no meio da realidade.

Podendo ser visto por outros,

Podendo tocar em outros,

Podendo sentar-se e estar de pé,

Mas a minha alma só pode ser definida por termos de fora.

Existe para mim — nos momentos em que julgo que efetivamente

existe —

Por um empréstimo da realidade exterior do Mundo

Da minha pessoa de dentro não tenho noção de realidade.

Sei que o mundo existe, mas não sei se existo.

Estou mais certo da existência da minha casa branca

Do que da existência interior do dono da casa branca.

Creio mais no meu corpo do que na minha alma,

Porque o meu corpo apresenta-se no meio da realidade.

Podendo ser visto por outros,

Podendo tocar em outros,

Podendo sentar-se e estar de pé,

Mas a minha alma só pode ser definida por termos de fora.

Existe para mim — nos momentos em que julgo que efetivamente

existe —

Por um empréstimo da realidade exterior do Mundo

Se a alma é mais real

Que o mundo exterior como tu, filósofos, dizes,

Para que é que o mundo exterior me foi dado como tipo da realidade"

Que o mundo exterior como tu, filósofos, dizes,

Para que é que o mundo exterior me foi dado como tipo da realidade"

Se é mais certo eu sentir

Do que existir a cousa que sinto —

Para que sinto

E para que surge essa cousa independentemente de mim

Sem precisar de mim para existir,

E eu sempre ligado a mim-próprio, sempre pessoal e intransmissível?

Para que me movo com os outros

Em um mundo em que nos entendemos e onde coincidimos

Se por acaso esse mundo é o erro e eu é que estou certo?

Se o Mundo é um erro, é um erro de toda a gente.

E cada um de nós é o erro de cada um de nós apenas.

Cousa por cousa, o Mundo é mais certo.

Do que existir a cousa que sinto —

Para que sinto

E para que surge essa cousa independentemente de mim

Sem precisar de mim para existir,

E eu sempre ligado a mim-próprio, sempre pessoal e intransmissível?

Para que me movo com os outros

Em um mundo em que nos entendemos e onde coincidimos

Se por acaso esse mundo é o erro e eu é que estou certo?

Se o Mundo é um erro, é um erro de toda a gente.

E cada um de nós é o erro de cada um de nós apenas.

Cousa por cousa, o Mundo é mais certo.

Mas por que me interrogo, senão porque estou doente?

Nos dias certos; nos dias exteriores da minha vida,

Nos meus dias de perfeita lucidez natural,

Sinto sem sentir que sinto,

Vejo sem saber que vejo,

E nunca o Universo é tão real como então,

Nunca o Universo está (não é perto ou longe de mim.

Mas) tão sublimemente não-meu.

Nos dias certos; nos dias exteriores da minha vida,

Nos meus dias de perfeita lucidez natural,

Sinto sem sentir que sinto,

Vejo sem saber que vejo,

E nunca o Universo é tão real como então,

Nunca o Universo está (não é perto ou longe de mim.

Mas) tão sublimemente não-meu.

Quando digo "é evidente", quero acaso dizer "só eu é que o vejo"?

Quando digo "é verdade", quero acaso dizer "é minha opinião"?

Quando digo "ali está", quero acaso dizer "não está ali"?

E se isto é assim na vida, por que será diferente na filosofia?

Vivemos antes de filosofar, existimos antes de o sabermos,

E o primeiro fato merece ao menos a precedência e o culto.

Quando digo "é verdade", quero acaso dizer "é minha opinião"?

Quando digo "ali está", quero acaso dizer "não está ali"?

E se isto é assim na vida, por que será diferente na filosofia?

Vivemos antes de filosofar, existimos antes de o sabermos,

E o primeiro fato merece ao menos a precedência e o culto.

Sim, antes de sermos interior somos exterior.

Por isso somos exterior essencialmente.

Dizes, filósofo doente, filósofo enfim, que isto é materialismo.

Mas isto como pode ser materialismo, se materialismo é uma filosofia,

Se uma filosofia seria, pelo menos sendo minha, uma filosofia minha,

E isto nem sequer é meu, nem sequer sou eu?

02/05/2014

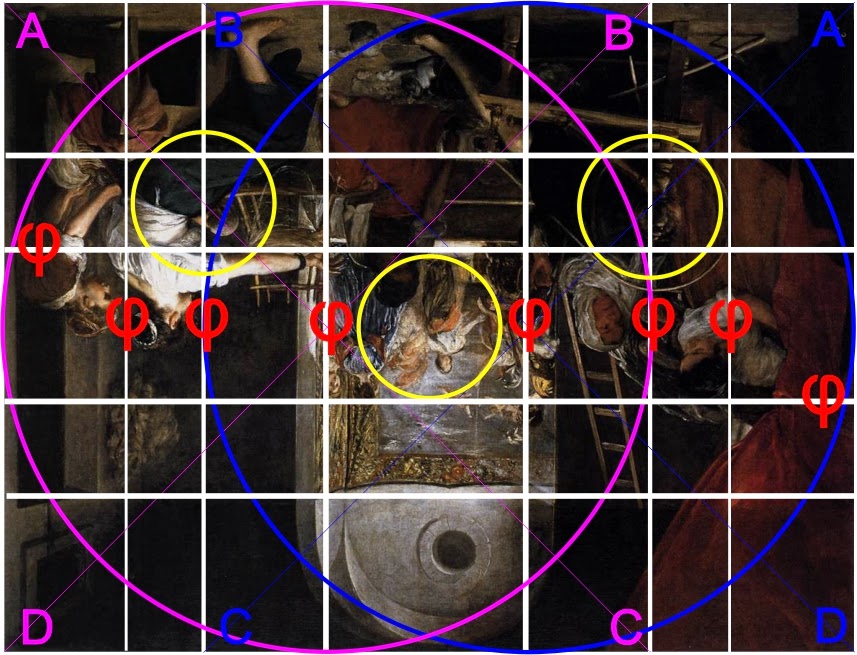

Diego Velázquez - Las hilanderas ou La fábula de Aracne, 1660.

How many solutions has the world?

Diego Velázquez.

Las hilanderas ou La fábula de Aracne, 1660.

Óleo sobre tela, 220 cm x 289 cm.

Ilidio Salteiro, 2014

26/04/2014

Diego Velázquez, A Fábula de Aracne, 1660

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, Las hilanderas, o La fábula de Aracne, 1655

– 1660.

Óleo sobre Lienzo, 220 cm x 289 cm.

O mito clássico de Aracne segundo

a narrativa de Ovidio (Metamorfosis, Libro VI, I)

14/04/2014

11/04/2014

09/04/2014

29/03/2014

Segurança? (III)

Safety in Numbers?

Um artigo publicado na Frieze, março 2014.

www.frieze.com/issue/article/safety-in-numbers/

Algorithms, Big Data and surveillance: what’s the response, and responsibility, of art? Jörg Heiser asked seven artists, writers and academics to reflect.

JORDAN ELLENBERG

In the current moment, we are experiencing a sense of

being tracked and measured by a cabal of machines whose genius is to distil the

particulars of our lives into a substance called ‘data’. The machines (and by extension their handlers) then use this

data to make inferences about our behaviour, our associations and our beliefs –

information that we haven’t intentionally revealed or which we perhaps don’t even

have access to ourselves.

Spooky, right? And seemingly antipodal to the kind of

insight that art is supposed to provide: mechanical where art is human,

repetitive where art is inventive. The machines that watch us can seem like

H.G. Wells’s Martians: ‘minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the

beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic’ which peer down

at the aggregate trail we leave in the informational substrate, and thus at us,

‘as a man with a microscope might scrutinize the transient creatures that swarm

and multiply in a drop of water’.

But what machines do with data is not so foreign. It

appears foreign, because when we talk about data we do so in the language of

mathematics: loss functions and kernels, logistic regression and Greek letters.

The language presents the same kind of difficulty for outsiders as the

international art-speak found on museum wall texts.

Quantitative surveillance has two main goals: to

classify and, having classified, to predict. And prediction comes down to this:

people are likely to do things in the future that people like them did in the

past. This principle – that we have tendencies, which are not inescapable but

which take some work or some luck to escape – is not the property of mathematicians.

How would novels function without it?

And the project of classification – which is to say

all the work that’s hidden in the word ‘like’ or the phrase ‘people like them’

– is nothing more than the project of analogy, which asks us to set aside the

boring observation that no two human beings (and, likewise, no two moments in

time, no two societies etc.) are identical to each other, and replace it with a

suite of more interesting questions, such as: in the space of human beings,

which people are near each other? Or, when are two things alike, in ways beyond

the obvious ones? That, of course, is a traditional artistic project too.

Big Data, automated behaviour prediction and

classification relate to traditional art forms as photography does to drawing and

painting. Photography isn’t there to replace artistic representation; in some

of its manifestations it’s a new form of artistic representation, and in all

its forms it’s something art can talk about, without acquiring expertise in

photoreactive chemistry or digital compression algorithms. It will be the same

story here.

And if you regard surveillance as a thing to be

resisted, take some comfort from the fact that Wells’s Martians were eventually

felled by terrestrial microorganisms. They were different from us on the

surface. But on the inside, where they were vulnerable, they were built much as

we are.

Jordan Ellenberg is Professor of Mathematics at the

University of Wisconsin, USA. He is a regular columnist forSlate and his book How

Not to Be Wrong (Penguin, 2014) is forthcoming.

27/03/2014

26/03/2014

Segurança? (II)

Safety in Numbers?

Um artigo publicado na Frieze, março 2014.

www.frieze.com/issue/article/safety-in-numbers/

Algorithms, Big Data and surveillance: what’s the response, and responsibility, of art? Jörg Heiser asked seven artists, writers and academics to reflect.

LAURA POITRAS

In a top-secret strategy paper published by The

New York Times in November, the US National Security Agency (NSA)

describes its current surveillance powers as ‘The Golden Age’(1) of signals

intelligence. This ‘Golden Age’ is one where our past is recorded and digitally

stored and our future is predicted. It is a system that seeks to know our

friends and networks, physical location, biometric data and what we read and

write. It is a system with ‘selectors’ and algorithms that watch our private

communications moving across the internet to build graphs which identify us as

‘targets’ for further, more invasive, forms of surveillance. Its goal is the

‘mastery’ of global communications.

This document and thousands more disclosed by Edward

Snowden reveal a fundamental threat to freedom.

As George Orwell and Michel Foucault both noted, one

of the goals of surveillance is to get inside our heads. They don’t have to be

watching – we just need to imagine they are. Every time we think twice before

entering a search term, distance ourselves from a person or topic that might be

targeted or censor our words, they win.

Surveillance targets our ability to think, create and

associate freely. When I sat down to write this, I disconnected my computer

from the internet to avoid my writing – the private process of formulating

ideas on a page – being monitored.

As surveillance powers expand, so will the circle of

people and activities monitored. I have no doubt we will see an increase of

surveillance-themed art work, but that misses the larger point. Snowden not

only revealed vast secret surveillance programmes, he revealed state control

and the power of the individual to resist it. Artists can respond by doing work

that resists control and conformity wherever it is encountered. Our responsibility as citizens is to make sure the

next generation does not have to censor its thoughts, actions and imaginations.

(1) ‘A Strategy for Surveillance Powers’, The

New York Times, 23 November 2013.

Laura Poitras is a filmmaker and journalist. She is

currently reporting on NSA abuses disclosed to her by Edward Snowden, and

editing the final instalment in a trilogy of films about post-9/11 America that

will focus on surveillance.

25/03/2014

Segurança? (I)

Safety in Numbers?

Um artigo

publicado na Frieze, março 2014.

www.frieze.com/issue/article/safety-in-numbers/

Algorithms, Big Data and surveillance: what’s the

response, and responsibility, of art? Jörg Heiser asked

seven artists, writers and academics to reflect.

Trevor Paglen, They Watch the Moon, 2010

TREVOR PAGLEN

Something fundamental is changing in the world of

images, and in the landscape of seeing more generally. We are at the point

(actually, probably long past) where the majority of the world’s images are

made by-machines-for-machines. In this new age, robot-eyes, seeing-algorithms

and imaging-machines are the rule, and seeing with the meat-eyes of our human

bodies is increasingly the exception.

Machines-seeing-for-machines is a ubiquitous

phenomenon, encompassing everything from infrared qr-code readers at

supermarket check-outs to the Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) cameras

on police cars and urban intersections; facial-recognition systems conduct

automated biometric surveillance at airports, while department stores intercept

customers’ mobile-phone pings, creating intricate maps of movements through the

aisles. Beyond that, the archives of Facebook and Instagram hold hundreds of

billions of photographs, which are trawled by sophisticated algorithms

searching for clues about the behaviours and tastes of the people and scenes

depicted in them. But all of this seeing, all of these images, are essentially

invisible to human eyes. These images aren’t meant for us: they’re meant to do

things in the world; human eyes aren’t in the loop.

All of this is new. Although Guy Debord’s spectacle

society has certainly not gone anywhere, the advent of ‘operationalized’

images is upon us. The 21st-century landscape of images and seeing-machines

directly intervenes in the surrounding world. Seeing-machines do

things-in-the-world not through the subtle ideologies of visual mythmaking and

fetishism, but through quantification, tracking, targeting and prediction.

How do we begin to think about the implications on

societies at large of this world of machine-seeing and invisible images?

Conventional visual theory is useless to an understanding of machine-seeing and

its unseen image-landscapes. As for art, I don’t quite know, but I have a

feeling that those of us who are interested in visual literacy will need to

spend some time learning and thinking about how machines see images through

unhuman eyes, and train ourselves to see like them. To do this, we will

probably have to leave our human eyes behind. A paradox ensues: for those of us

still trying to see with our meat-eyes, art works inhabiting the world of

machine-seeing might not look like anything at all.

Trevor Paglen is an artist.

24/03/2014

22/03/2014

21/03/2014

Publico das coisas da arte & religião alternativa para ateus

«One theme

that runs through the narratives of Seven

Days in the Art World is that contemporary art has become a kind of alternative

religion for atheists» (Sarah Thorntom, Seven Days in the Art World, W.W.

Norton Company, 2008, p XIV).

Sendo Portugal um povo de formação eminentemente cristã,

percebe-se porque não existe público para «as coisas da arte.»10/01/2014

Takashi Murakami’s New York Studio Is Definitely Not Psychedelic

Japanese

Superflat founder Takashi Murakami’s New York studio and office, an

outpost of his company Kaikai Kiki, is pretty much the opposite of the artist’s

crazily colorful, hallucinogenic work. The building, created by HWKN architects,

is elegantly minimal, precisely controlled, and flexible for art production

purposes.

04/01/2014

02/01/2014

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Arte pela Arte - 2025

arte pela arte - 2025 Quando na conferência que foi dada na Biblioteca Municipal Álvaro de Campos em Tavira foi-me perguntado algo que tin...

-

Ilídio Salteiro, 2019. Óleo sobre papel, 150 cm x 200 cm. Dez palavras para catorze pinturas Ilídio Salteiro, Li...

-

Ruth ’ s Room Il í dio Salteiro - Installation Fotografia de Tela Leão Collector Room Thirty years in 2015 correspond ex...